This article “Get forensic if you’re buying a franchise” was originally published in the The Australian Financial Review, by Michael Bailey.

For anybody looking to buy themselves a job or an investment in franchising, the Senate’s current inquiry into the sector should be required viewing.

There are good news stories among the 300 submissions the inquiry has received. “We have worked very hard and taken risks to earn the success we have achieved, but we could not have done this without the ever-present support of our franchisor,” wrote Mark Skews, the Mermaid Beach franchisee for parcel courier Pack & Send.

However the urge to “buy the dream” of running your own business should be tempered by the tales of deception and financial ruin. “7-Eleven Australia’s business is based on franchisees’ slavery” is a direct quote from one submission to the inquiry, from a group claiming to represent more than half the disgraced convenience chain’s 400 franchisees.

“Franchising is a failed system run by wealthy corporations who only have their interests at heart,” wrote Kyle Hudspeth, a former Croissant Express franchisee. “Mum and dad investors work themselves to the bone, only to be left destitute with no one to consider their plight.”

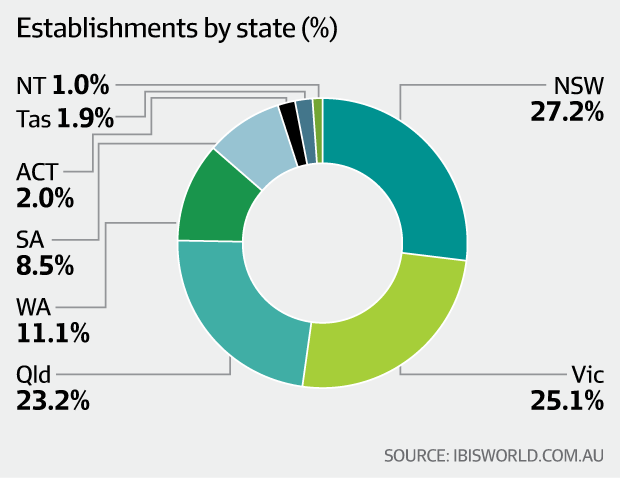

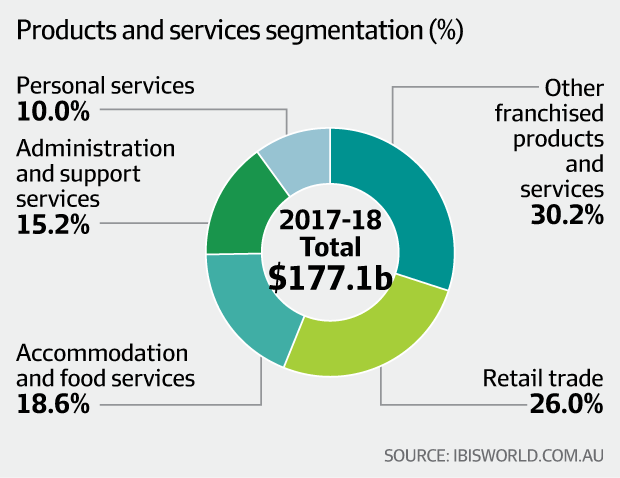

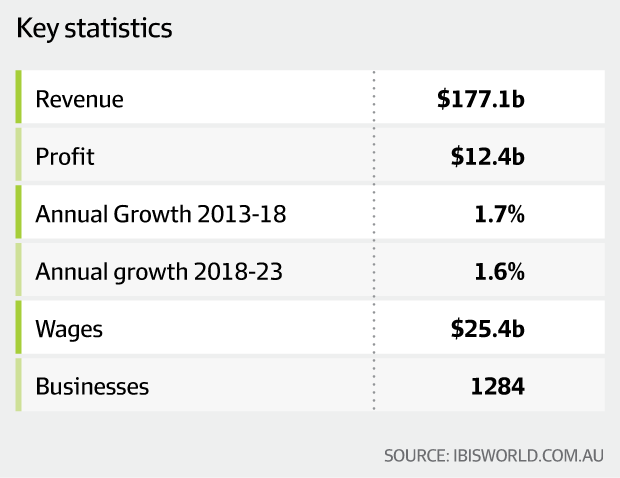

It is arguable how representative these horror stories really are of Australia’s franchising sector, one of the world’s largest per capita with 1100 franchise systems representing 80,000 customer-facing businesses, employing 460,000 and expected to turn over $180 billion in 2018-19.

“Franchising in Australia is like any industry,” wrote Pack & Send’s Skews. “Ninety-nine per cent are wonderful hard-working people, and one per cent are bad apples of which everyone takes notice, without rising above to view the industry as a whole.”

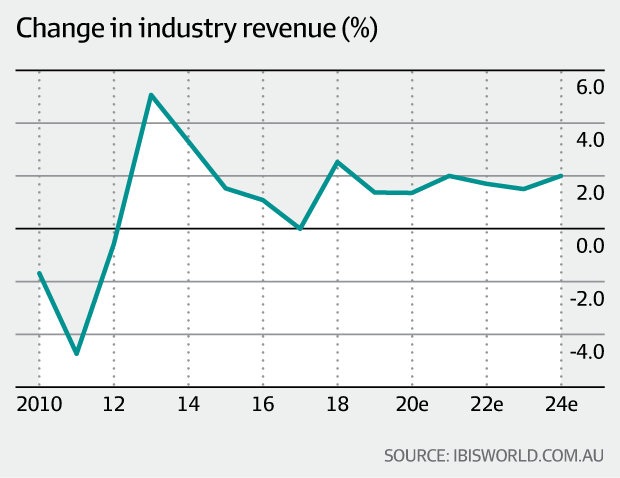

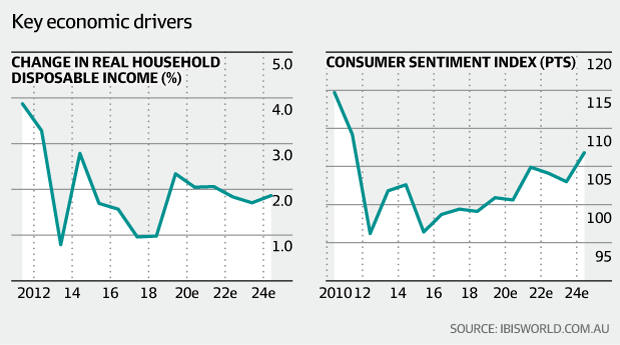

The macroeconomics support the view that franchising is an investment opportunity worth the due diligence.

Service-based franchises – such as those that provide health, nutrition and wellbeing services – in particular are likely to benefit from a forecast rise in disposable incomes and decline in spare time over the next five years, according to IBISWorld senior industry analyst Bao Vuong.

The research house is projecting franchise sector revenue to increase at an annualised 1.7 per cent over the five years through 2023-24, to be worth $195.4 billion.

Three in four small businesses established within a franchise network were still operating after five years, according to Franchise Council of Australia chairman Bruce Billson, versus one in four stand-alone small businesses.

“Franchising is predicated on an adult-to-adult, mutually beneficial partnership between franchisor and franchisee, where one brings a proven tool kit, the other brings their entrepreneurial flair and field intelligence,” Billson says.

However that high survivorship number, while technically correct, may be painting too rosy a picture of the average franchisee investment, according to Michael Fraser of consultancy Franchise Redress.

“What these franchise lobbyists fail to include in their analysis is that franchisees are bound by franchise terms in their agreements, where they must remain operating until the end of their franchise term or sell their business,” Fraser says.

“While an independent operator could effectively walk away, the franchise operator may have no choice but to continue operating or even renew their franchise agreement while incurring huge losses in their business. An independent business has the risk of being pursued for payments on their lease, however a franchisee also has the added risk of being sued by the franchisor.”

Hudspeth is a case in point. He bought into the Croissant Express network in 2011 but gave up on the last of his two cafes in 2016 after Young Rich Lister Sean Tomlinson bought the Perth chain in 2013 as a captive customer for the point-of-sale system that’s the basis of his $154 million fortune. Now creditors are seeking to wind up Croissant Express and Hudspeth is being sued for $250,000 for breaking a 10-year franchise agreement six years early.

Do your homework

Yet buying a franchise remains a great investment if you do your homework, according to Sue Campbell, whose consultancy Franchise Right has designed or tweaked systems from physiotherapy chain Back In Motion to McDonald’s.

Franchisees need to come in with their eyes wide open to the opportunity, says Sue Campbell. Chris Hopkins

“The Franchising Code of Conduct offers sufficient protection to franchise investors, especially since it was updated in 2015 to oblige good faith dealings between franchisee and franchisor,” she says.

“But it’s not meant to replace due diligence and hard work. Franchisees need to come in with their eyes wide open to the opportunity.”

As with any investment, Campbell says potential franchisees must be clear about their end goal – whether that is maximising income, improving job satisfaction or creating an asset to be sold or passed down to the next generation.

Given the substantial investment involved – Griffith University’s Franchising Australia 2016 report found the average total start-up cost for a new retail franchise unit was $287,500, or $59,750 for a non-retail franchise – Campbell urges would-be franchisees to take into account the big risk ahead.

The banks grant “accreditation” to only a handful of the most established franchise systems, she points out, meaning that most franchisees will be required to put up their home as security. However interest rates are typically more in line with standard commercial rates than the higher rates payable by new standalone businesses.

So the next steps are research, research, research.

Although anybody wading through the Senate inquiry submissions might have difficulty believing it, the disclosure document that franchisors have long been obliged to give potential franchisees under the code of conduct is “your best friend” when it comes to weeding out bad systems, Campbell maintains.

Vital clues

The four pieces of information the disclosure document must contain, according to the code’s regulator the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, are:

- Details of legal proceedings against the franchisor or its directors;

- The franchisee’s costs to start operating the franchised business and other payments or fees they may be required to make;

- Details of the arrangements that will apply when the franchise agreement comes to an end (including whether the franchisee will have an option to renew or extend the agreement); and

- Contact details of current as well as former franchisees.

Only this last requirement is unhelpful, says Campbell. “Any list of franchisees a franchisor gives you to ring, throw it out,” she says. “Look all their locations up online and ring as many of them as you can. You’ll soon get a sense of how happy everyone is.”

Find your target store in person, advises Franchise Redress’s Michael Fraser. He’s seen many franchisors refuse to give a potential investor a store’s full history, citing a previous owner’s wish for confidentiality as is technically allowed under the code.

“But you have to know why that last person left. Just go into the shopping centre and ask the security guard or info desk,” he says. “With one Donut King we were investigating, it was the guys in the guitar shop next door that told us the franchisees couldn’t afford to stay and walked away.”

Franchise investors should also insist on working in their predecessor’s business for at least a week, if possible, says Fraser.

“It’s even worth paying them something for that inconvenience, because so much truth comes out. You might have insisted on wage records, but once you’re in there you might see the owner has their family working in there for nothing, so maybe that’s another $1400 a week you have to add to expenses.”

The absence of complaints from McDonald’s franchisees at the inquiry was in part due to the network’s rigorous preparation of potential franchisees, says Fraser, which included them working in the stores for a year before they were approved to buy in.

Query financial model

Investors should not be afraid to ask for the franchisor’s own financial model and future business plans in writing, says Campbell. Most franchisors will want to set their franchisees up for success and will provide them, she says, but it’s still worth getting expert help to dissect them.

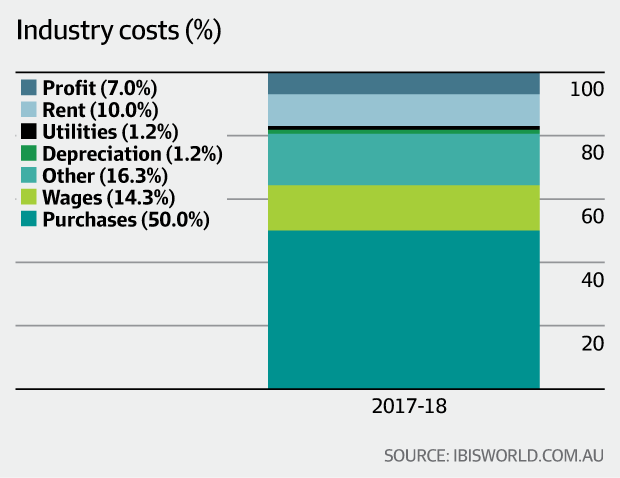

“The allocation of marketing fees, for instance, should be crystal clear, and if a model is structured on incoming lumps of cash from selling franchises, that is not sustainable.”

Yet rapid expansion that cannibalised existing franchisees was the modus operandi of most franchise networks once they became publicly listed or fell under private equity ownership, says Fraser. He says anything but a family-owned network should be a “massive red flag” to investors.

He has proposed the introduction of a corporate “franchisor’s licence”, which the ACCC would have the power to revoke for unconscionable conduct, as an alternative to protecting investors with yet more regulation.

“Retail Food Group would have lost their licence long ago,” he says of the scandal-plagued owner of Michel’s Patisserie and Donut King.

Or investors could be protected by a version of the “lemon laws” proposed for the car sales industry, says Jenny Buchan, a franchising expert at the University of NSW Business School.

Under such a protection, the buyer of a franchise in an unworkable, undisclosed condition should be able to get their money back and walk away. Fraser suggests such a get-out clause should even apply to major expenses not flagged with franchisees – such as the $60,000 faster ovens Domino’s Pizza expected its franchisees to purchase last year.

Most franchise investors won’t wait to see if the senate inquiry recommends such added protections, says Buchan.

“The people open to franchising opportunities tend to be eternal optimists, so they won’t think these examples they read about will apply to them,” she says. “You’ll still have people getting redundancies, people immigrating and needing to start a business to get permanent residency, and more power to them.

“Many of my students are still drawn to franchising because done well, it’s one of the best ways you can get a new concept to market.”